US President Donald Trump's recent announcements of tariffs on imports of steel and aluminium as well as on an array of consumer goods from China have sparked a frenzy of concern over the risk of a global trade war.

Vanguard expects minimal direct economic impact from the new tariffs, however. We feel their real importance lies in the broader and longer-term implications for international trade policy.

Putting the tariffs in context

The Trump administration first announced it was imposing import tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium – products that together represent less than 2% of total imports to the United States. And even that estimate is high, as Canada, Mexico and other allies including the European Union have been temporarily exempted.

On 22 March, the administration announced a package of taxes and trade penalties on goods from China. As with the tariffs on steel and aluminium, these tariffs would likely affect only a small fraction of bilateral trade between the world's two largest economies.

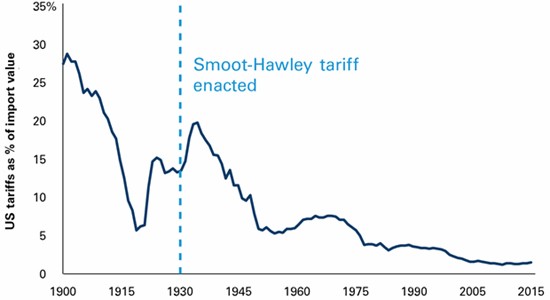

To better understand what escalation of these disputes might look like, it's helpful to consider trade in a historical and global context.

US tariffs have been falling since the 1930s and have been below 5% for more than four decades, as shown below. According to the World Trade Organisation's latest report on tariffs, the current average US tariff is 3.5%, the second-lowest in the G20.

Note: Data shown are annual from 1900 to 2015. Source: US International Trade Commission.

Although the United States has in place non-tariff trade measures such as anti-dumping and national security safeguards, it remains one of the world's least protectionist countries, alongside the members of the European Union.

Some market observers extrapolate the policy tilt of the tariffs to mark the onset of a trade war, similar to the vicious cycle sparked by the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which dramatically reduced trade flows and economic growth in the early years of the Great Depression.

Given the history of lowering trade barriers and realising the benefits of economic integration, Vanguard believes it is unlikely that the current US administration will dramatically shift trade policy at the risk of disrupting domestic growth.

Benefits of a slight rise in tariffs fast diminish

Although we assign a trade war scenario a low probability, our analysis in a 2017 Global Macro Matters research paper (“Trade status: It's complicated”) estimated the impact of varying escalations in trade tensions. A slight increase in tariffs has a short-term marginal benefit to the issuing economy in the absence of retaliation. These benefits quickly diminish, however, and can be offset by retaliatory tariffs and market volatility.

With tariff increases offsetting one another, the end result would be higher consumer prices and lower growth from reduced trade activity – a lose-lose scenario.

Although unlikely, a trade war environment could reduce US GDP by 1.7 percentage points and increase inflation by 0.4 of a percentage point annually. In this case, the impact would be significant enough to force the US Federal Reserve to pause its tightening of interest rates and choose between suppressing excessive inflation and bolstering low growth.

Tariff fallout could put US in lagging position

Outside of these estimates of the direct impact on the US economy, reduced cooperation on trade over the next few years could hurt cross-border investment flows and place the United States in a lagging rather than a leading position in future economic and political partnerships.

Investors can reasonably assume that trade rhetoric will remain a source of volatility throughout 2018 as the Trump administration tries to set a new course on trade policy without triggering retaliation from America's global trading partners.

Although trade wars are still a low likelihood, it is worthwhile to closely monitor policy decisions – and the responses to them – for signs of escalation.

27 March 2018

vanguardinvestments.com.au